From unattainable house prices to disappointing pay rises, the financial challenges faced by young adults can seem daunting.

How much wealth your parents have is likely to matter more than it did for older generations. Here's why.

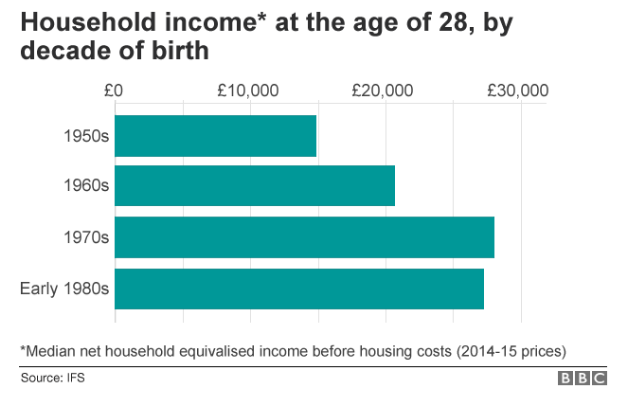

1. Income growth has stalled

It used to be the case that young adults could expect to start their working lives with higher incomes than those born earlier.

This is because incomes normally rise over time, as the economy grows.

Then we had the financial crisis of 2008.

The upshot is that today's young adults are the first generation since at least World War Two not to start their working lives with higher incomes than those born before them.

[See The economic circumstances of different generations: the latest picture (figure 1), by Jonathan Cribb , Andrew Hood and Robert Joyce, for data and more information.]

For example, someone born in the 1980s could expect a household income of £27,000 at the age of 28, compared with £28,000 for those born in the 1970s.

The figure was £21,000 for those born in the 1960s and £15,000 for those born in the 1950s.

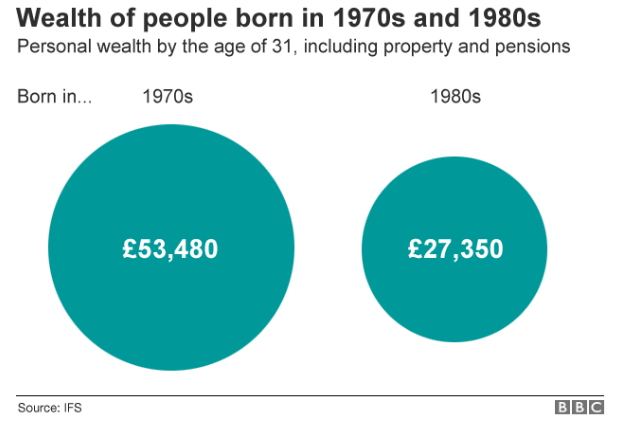

2. The wealth of young adults has halved

Despite having about the same income, those born in the early 1980s are much less wealthy than those born in the 1970s were at the same age.

[See The economic circumstances of different generations: the latest picture (figure 5), by Jonathan Cribb , Andrew Hood and Robert Joyce, for data and more information.]

By their early thirties, the 1980s generation had accumulated wealth of about £27,000 each, on average.

By the time they had reached the same age, the 1970s generation had twice as much wealth on average - £53,000 each.

A large part of the explanation is that an individual's wealth is mainly made up of property and pensions - and younger adults are faring well with neither.

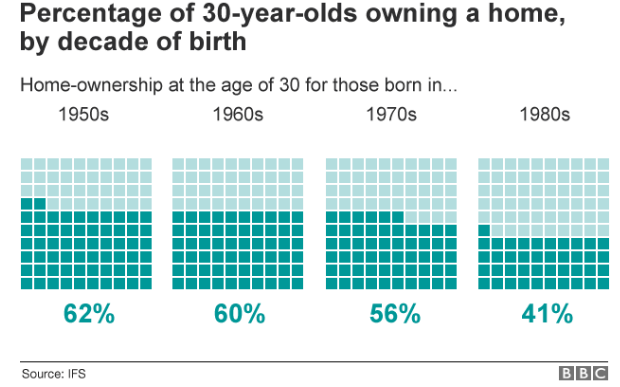

3. Young adults are much less likely to own their home

At the age of 30, 40% of people born in the early 1980s were owner-occupiers, down from 55% of those born in the 1970s.

Home ownership rates were higher still among earlier generations, with six out of 10 people born in the 50s and 60s owning their own homes at the age of 30.

[See The economic circumstances of different generations: the latest picture (figure 7), by Jonathan Cribb , Andrew Hood and Robert Joyce, for data and more information.]

Similarly, the Local Government Association reported in December that just 20% of those aged 25 own their own property, compared with 46% two decades ago.

The lower home ownership rate doesn't just explain why young adults have lower wealth now. It also means they are likely to be poorer as they get older, because fewer of them will benefit from future increases in house prices.

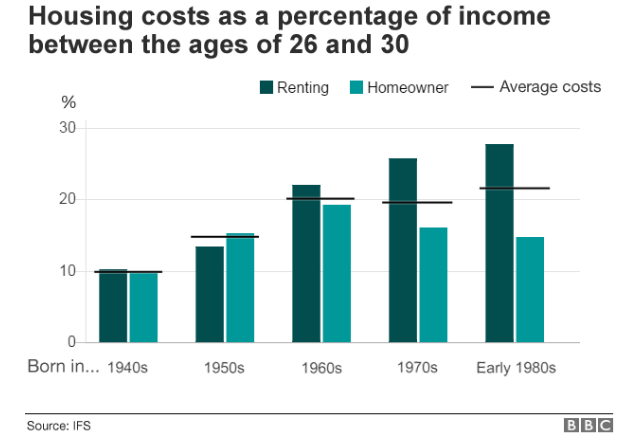

4. Rents are taking a greater share of income

In their late twenties, renters born in the early 1980s were spending 28% of their income on housing costs.

At the same age, those born in the 1960s were spending 22% of their income on rent. Those born in the 1950s spent 13% and those in the 1940s just 10%. Part of the rising costs of renting is explained by the decline of social housing.

[See The economic circumstances of different generations: the latest picture (figure 3), by Jonathan Cribb , Andrew Hood and Robert Joyce, for data and more information.]

For today's renters, it seems likely that raising a deposit is a greater barrier to home ownership than actually paying a mortgage.

Lower interest rates mean housing costs for young homeowners have fallen and they are quite likely to be paying much less than renters relative to their incomes. Mortgage interest costs for homeowners born in the early 1980s amounted to just 15% of income.

Of course, the low interest rates that have benefitted homeowners are themselves likely to be one of the factors pushing up house prices.

5. Pensions are getting smaller

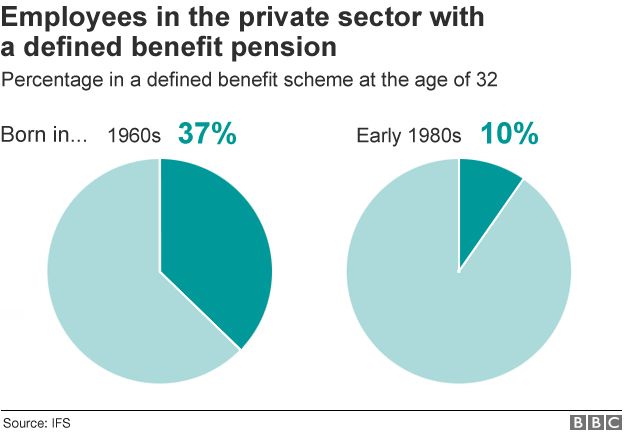

The vast majority of young adults working in the private sector will never have pensions as generous as those enjoyed by their older colleagues.

This is because most employers have closed defined benefits pension schemes, which typically see employees paid a set proportion of their average or final salary when they retire.

The schemes that have replaced them are typically much less generous.

[See The economic circumstances of different generations: the latest picture (figure 9), by Jonathan Cribb , Andrew Hood and Robert Joyce, for data and more information.]

In their early thirties, fewer than one in 10 private sector employees born in the early 1980s were active members of a defined benefit scheme.

This compares with nearly four out of 10 workers born in the 1960s.

In 2015, 90% of those in defined benefit schemes received an employer contribution equivalent to 10% of their earnings or more, compared with only 13% of those in other schemes.

6. Inheritance matters more than ever

With stalled incomes, lower home ownership and less generous pensions, it is easy to see that young adults have little to cheer about financially.

But those older, wealthier, generations are increasingly seen as the ones likely to provide a secure future.

[See Inheritances and inequality across and within generations (figure 3), by Andrew Hood and Robert Joyce, for data and more information.]

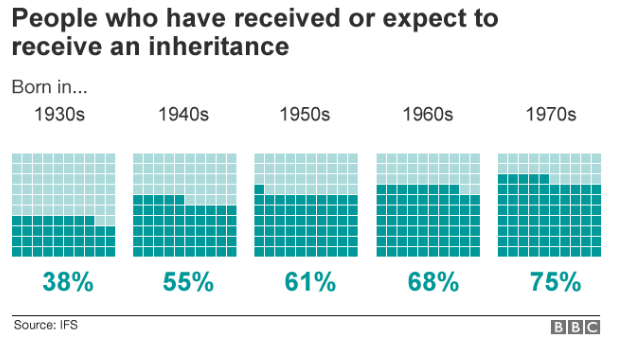

Of those people born in the 1970s, 75% have either received or expect to receive an inheritance.

This figure has grown steadily over the decades and has doubled since the 1930s, when just 38% of people expected an inheritance.

Our data doesn't allow us to look at those born in the 1980s or 90s, but there is no reason to think this trend has not continued.

7. But those with higher income are most likely to inherit

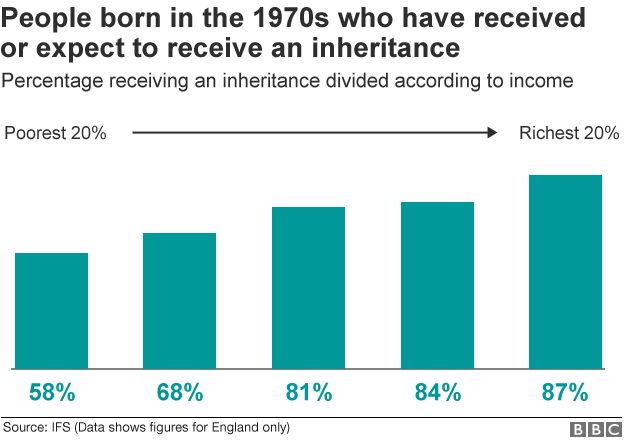

Within each generation, most inherited wealth goes to those who are already comparatively well-off.

Among the 1970s generation, nine out of 10 people whose income is in the top 20% have received or expect to receive an inheritance.

This compares with six out of 10 among those whose income is in the bottom 20%.

[See Inheritances and inequality across and within generations (figure 14), by Andrew Hood and Robert Joyce, for data and more information.]

Data is not yet available for those born in the 80s or 90s.

So, for all the attention on inequality between generations, family ties mean a large chunk of the wealth held by older generations is likely to flow down to younger generations.

But most of that wealth will flow to those who are already well-off, potentially widening inequality within the younger generation.

It looks like we're heading for a future where how much wealth your parents have matters more than it used to.

This article was prepared for and first published on the BBC's website. The graphics on this page are reproduced with permission of the BBC and should not be reproduced elsewhere without permission.